Partisan Divide Among Republicans, Democrats About Covid Risks

What are the chances somebody with COVID-19 must be hospitalized? Your perception may vary depending on your political leaning.

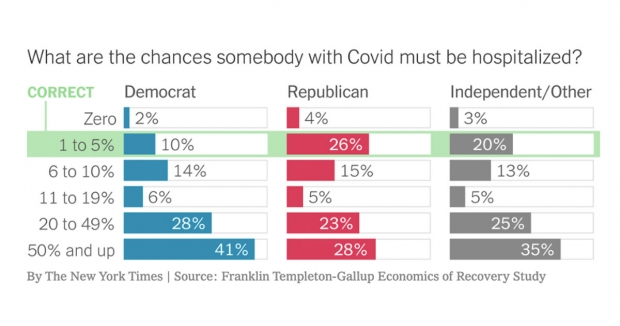

The chances of being hospitalized from COVID-19 are between 1-5%, but Democrats overestimate the risk: 41% of Democrats think the chance of hospitalization is 50% or more, while 28% of Republicans think the chances are that high. Republicans were more likely to give the correct answer — 26% got it right, compared to 10% of Democrats.

These numbers are highlighted by The New York Times (Lean Left) in a graphic below. It showcases survey results from 35,000 Americans who responded to the Franklin Templeton-Gallup Economics of Recovery Study.

According to the study authors, “less than one in five U.S. adults (18%) give a correct answer of between 1 and 5%” for COVID-19 hospitalization risk.

While Democrats are more likely to overestimate hospitalization risk, Jonathan Rothwell and Sonal Desai, who documented the study, say Democrats are more likely to correctly state that COVID can be spread by people without symptoms (23% of Democrats say COVID can’t be asymptomatically spread, while 37% of Republicans say it can’t), and to more accurately assess that the overall mortality risk of COVID-19 is more severe than “other common causes of death,” such as influenza and automobile accidents.

In early September, 41% of Republicans said they thought the flu had caused more deaths than COVID-19 in 2020, while just 13% of Democrats said so. “Even automobile accidents were said to cause more deaths, which is also untrue according to CDC data,” Rothwell and Desai write. “Likewise, just over one in three Republicans (37%) deny that it is definitely true that COVID can be spread by people without symptoms compared to only about one in four (23%) Democrats.”

(The Franklin Templeton-Gallup Economics of Recovery study, notably, did not appear to ask respondents about perceived COVID-19 death risk in relation to the actual top two leading causes of death in the U.S. since the start of the pandemic, cancer and heart disease. COVID was the third leading cause of death during that time, according to CDC mortality data. The flu and pneumonia was the number 10 leading cause of death, and car accidents did not crack the top 10.)

The New York Times notes that “some of these misperceptions reflect the fact that most people are not epidemiologists and that estimating medical statistics is difficult,” but the perceptions still have real-world implications for how people behave and what they believe about vaccines, vaccine mandates, mask-wearing, social distancing and lockdowns.

“Political affiliation has deeply shaped how people understand and respond to the pandemic,” write Rothwell and Desai. “As noted in parallel research from Gallup [Center bias] and others, attitudes about COVID’s risks and willingness to engage in disease-suppression behaviors like social distancing are strongly related to politics, even more so than to local exposure to the virus or demographic factors that predict severe health consequences from the virus like age or pre-existing medical conditions.”

Beliefs about the severity of COVID are intricately tied to our political worldviews and the filter bubbles we live in.

If you read content that plays up the severity of covid, you may have an overinflated estimation of hospitalization risk; or perhaps you are in a bubble of content and people who accurately assess the hospitalization risk, but have an inaccurate perception of covid as a leading cause of death, and thus downplay that element (of course, some question the CDC mortality data, arguing that severe illness and deaths from other causes have been erroneously attributed to COVID, inflating the numbers).

As long as COVID-19 continues to be a global issue, we will see vastly different assessments of the risk, and vastly different beliefs about the appropriate measures to take as a result.

You can read the full study on misinformation and COVID-19 here.

Julie Mastrine is the Director of Marketing at AllSides. She has a Lean Right bias.

This piece was reviewed by Henry A. Brechter, Managing Editor (Center bias) and Andrew Weinzierl, Research Assistant and Data Journalist (Lean Left).

May 21st, 2024

May 16th, 2024

May 16th, 2024